As Bangladesh turns 50 this year, the country has much to celebrate. Its human-development progress has been exceptional compared to that of its South Asian neighbors. Sustained economic growth has reduced extreme poverty – not least because the early introduction of mobile phones at the grassroots level enabled the modernization of previously unconnected village economies. Moreover, Bangladesh has become more resilient to natural disasters such as cyclones and floods, and the state’s capacity to manage crises also has improved.

Bangladesh’s virtuous cycle of technology-aided development stems from decades of sustained state-NGO collaboration, combined with an emphasis on bottom-up initiatives to empower female entrepreneurs. This model has also given the country an unexpected advantage in managing the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although many developing countries rapidly implemented new cash-transfer programs in response to the pandemic, not all of these schemes have been equally effective in reaching the poor. Pakistan and India both relied on the traditional banking system to disburse cash benefits, while China opted to digitize transfer services. But both methods have excluded significant segments of the population.

Bangladesh therefore chose a different path by using mobile money to bridge the double divide in access to digital technology and formal banks. The government recently ended the age-old practice of transferring money under safety-net programs to beneficiaries’ bank accounts. Instead, mobile financial services providers today cover 98% of the country’s mobile-phone subscribers. Nearly 80% of users live within one kilometer (0.6 miles) of an MFS agent, stationed in local grocery stores and mobile recharge points. The agent manages e-money and cash withdrawals from mobile money accounts, as well as assisting with account registration. The MFS regulation also allows money transfers to cellphone owners who do not have a mobile-money account, thus ensuring that even those without internet access can benefit.

MFS could potentially revolutionize social-service delivery in South Asia, where as many as 625 million adults have no bank account. Bangladesh, with high teledensity and (by regional standards) a relatively small gender gap in mobile-phone ownership, stands to benefit. But other countries’ use of mobile-phone payment technology to disburse COVID-19 funds has been limited by lower coverage and a lack of mobile-money agents.

Pakistan, for example, lags behind Bangladesh in terms of the number of mobile cellular subscriptions per hundred inhabitants. According to the World Bank, only 50% of Pakistani women own a mobile phone, compared to 61% in Bangladesh. Furthermore, just 7% of the population has a mobile-money account, whereas 21% of Bangladeshis do.

The explaination for this uneven spread of mobile telecommunications technology across South Asia is the effort by Harvard University’s Iqbal Quadir, who strongly believes in “bottom-up entrepreneurship.”

Bangladesh’s dynamic telecoms sector is the product of an inclusive development strategy. The end of Bangladesh’s military dictatorship in the 1990s paved the way for a range of NGO-led social innovations and market-led solutions to create jobs and deliver critical public services. The then-newly elected government of Sheikh Hasina ended the state monopoly in the telecommunication sector, issuing licenses to Grameenphone and two others.

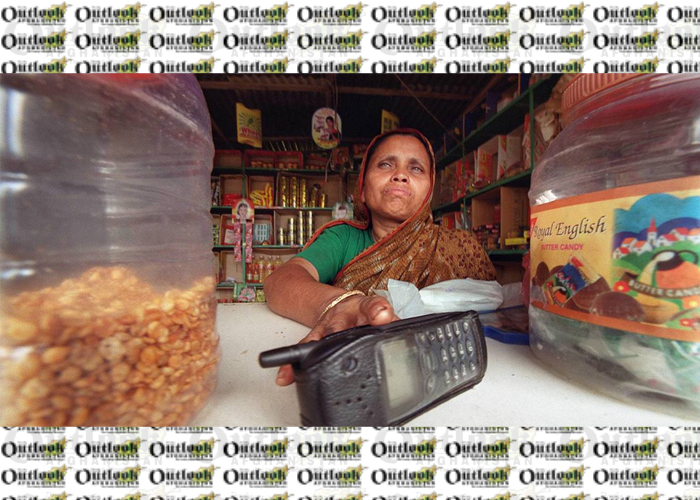

But the key to inclusive development was the simultaneous promotion of tele-entrepreneurship targeting village women. The country’s large number of mobile-money agents and rapid growth in cellular subscriptions reflect the unorthodox model of first-generation cellular providers, which focused on grassroots women entrepreneurs.

Crucially, Quadir, a budding tech entrepreneur at the time, persuaded Grameen Bank to enter the rural telecom market. Together, they set up Grameenphone in 1997 to help subscribe thousands of rural women to mobile service delivery in remote locations well beyond the reach of the state-owned telephone network. With additional microcredit support from Grameen Bank and BRAC, millions of women set up microenterprises, while telecommunications technology connected previously isolated rural areas with cities and markets. Grameenphone’s Village Phone Program not only connected millions of people across thousands of Bangladeshi villages and empowered rural women; it also laid the foundation for the subsequent emergence of many commercial service providers, including bank-led mobile money firms such as bKash.

Pakistan, by contrast, has largely lacked community-level social entrepreneurship in the telecommunications and mobile-money sectors, as well as innovative NGO programs promoting female entrepreneurs. Differing levels of support for bottom-up entrepreneurship partly explain the divergent path of women’s development following Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971. According to World Bank data, at least 10% of Bangladeshi women have a mobile-money account, compared to only 1% in Pakistan. And while 36% of women in Bangladesh have a bank account, only 7% in Pakistan do.

The early emergence of grassroots tech entrepreneurs in Bangladesh helped to spread telecommunications technology in low-literacy rural communities. This perhaps explains the explosive growth in Bangladesh’s mobile subscription rate in the past two decades (from 0.2 to 101.6 per hundred inhabitants) and why the country is currently leading Pakistan in terms of socioeconomic development. The end result is a market solution to a long-term development challenge, including the emergence of a responsive state in times of crisis.

Had Bangladesh not adopted a long-term approach to technology development and instead relied only on digital and conventional finance for public-service delivery, new technologies such as mobile money would have left many citizens excluded during the pandemic. Other countries seeking technology-based solutions to foster a post-pandemic recovery – not least developing Asian and African economies with millions of “unbanked” people – should thus invest early in social infrastructure. Bangladesh at 50 offers a blueprint for how to do it.

Home » Opinion » The Benefits of Bottom-Up Entrepreneurship

The Benefits of Bottom-Up Entrepreneurship

| M. Niaz Asadullah and Mishkatur Rahman