Afghanistan has undergone a massive transformation ever since the first bombs were dropped on Taliban positions and sent them scurrying for cover in the winter of 2001. Only a few weeks earlier few believed that an entirely different future would be awaiting Afghanistan. At the time, it was all doom and gloom with Taliban having captured almost 90% of Afghanistan's territory. The world was slowly coming to terms with a fundamentalist regime in Afghanistan whose likes had not existed anywhere in the world for at least the preceding one century.

What was surprising and tragic was that what the Taliban stood for and did was and is still alien to Afghanistan. They were and are a historical aberration. This is borne out by the fact that in contemporary history of Afghanistan, the kind of violent, reactionary and fundamentalist reading of religion that Taliban adhere to has largely been absent. Extremism and radicalism based on religion is a very recent phenomenon in the history of Afghanistan and Taliban remain as its only practitioners.

In the hay days of Mujahideen war against the Soviet occupation, Mujahideen, in areas that fell under their influence, practiced a kind of governing that was a far cry from what the Taliban did. Their style of governing was much more liberal and did not seek to impose the kind of interpretation of Islam that the Taliban did. In the north and in the areas under the influence of Gen. Dustom, for example, women were indeed allowed to work outside of their homes and it was even encouraged. So the Taliban clearly stand as a major historical aberration that does not have roots in the Afghan society, culture and politics. The question that arises here is what are the origins of this movement?

The upsurge in the culture of madrassa in the Af-Pak border regions in 1980s and 1990s stands as a very significant reason. In that era madrassas transformed from impoverished traditional seminaries into a vast and sprawling, strategic enterprise that mushroomed and absorbed generous funding pouring in from around the world. In the heat of the Cold War rivalries and the West's resolve to bleed the Soviets, that transformation was quick and profound.

The Af-Pak border regions were, therefore, fertile grounds for a drastic expansion of religious radicalism. Its genesis, however, lies in the kind of Islamic jurisprudence that is mainly practiced in the Subcontinent. The Deobandi School of jurisprudence that emerged in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh in British Raj centuries ago was and continues to be the genesis of the Taliban movement of today.

The influence of these Deobandi and other schools of jurisprudence were significant in Af-Pak border regions throughout contemporary history of the region. In 1970s and 80s too, these border regions were culturally much closer to the Subcontinent than Afghanistan. Even today, culturally, socially and linguistically, these regions are indeed part of the extended domain of the Subcontinent – and of course not Afghanistan proper.

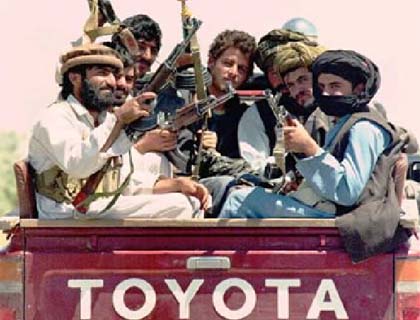

It is, therefore, clear without saying that the Taliban, as an ideological entity, have more in common with the Subcontinent and not Afghanistan, although an overwhelming majority of Afghan Taliban is comprised of Afghans from the southern belt. Inside Afghanistan, the coming to prominence of Taliban in the past two decades amounts to a cultural and ideological coup deta. In 1990s, the people of Afghanistan as well as many Mujahideen factions were taken by surprise when the Taliban grew out of shadow swiftly and furiously and, almost overnight, became claimants to absolute power in Afghanistan.

Every coup deta is short-lived – more so in Afghanistan. This is a lesson learnt from the pages of history. So what about this ideological and cultural coup deta that the Taliban pulled off? It does not seem to be short-lived after all! More than a decade since they were thrown out of power and into the deserts and oases of Waziristan-Baluchistan neverlands, they have come back and have done it with plentiful vengeance.

From Laghman to Logar and onwards to Kandahar, they seem to be in charge in many places. So what is the reason for this coup deta becoming so long-lasting? The fact is that the Taliban have become fairly strong and their presence extended chiefly due to lack or weakness of viable alternatives. In the wilderness of Afghanistan of today, Taliban are strong because their alternatives (one can be the government of Afghanistan) are weak or absent – Taliban per se do not have the inherent power to stay on and maintain the position of prominence that they have been able to hold onto for quite so long now.

The levers of support for the Taliban are strong. So are the forces that are propping up this movement with abundant logistical and ideological support. If these levers of support were to be withdrawn, you could see this colossal movement and massive insurgency starting to crack up and crumble from within. In the absence of outside support, this movement would be quick to melt away as has done the snow in Kabul under the sun of the waning days of Afghan winter.

The best way to fight off the Taliban or at least to keep them at bay is to gradually place them in a cultural and ideological vacuum. No victory of the sort that Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka could achieve against the LTTE would be doable in Afghanistan. If we wait for the day when the military might of Afghanistan or that of its allies gets strong enough for crushing the Taliban, that day would never arrive.

The way forward, of course, is to create the necessary conditions for making Taliban redundant in a cultural and ideological void and vacuum that few would be buyers of what they have on offer. This would be in the southern belt of Afghanistan where sympathy for Taliban is strong. In Afghanistan proper, there is no issue of sympathy as evident during the resistance years against the Taliban. Creating this cultural and ideological void requires strengthening the alternatives in front of what the Taliban have on offer.